Deep in the streets of Kitintale, there is a small library where the dreams, letters, and learning of a community that has seen its young people grow up amidst illusions, challenges overcome, yearnings, four wheels, and a lot of asphalt.

There is a library that is twinned with a skateboard park that since 2006 has been changing the views of the neighborhood and has transformed the lives of all the inhabitants around it. To get to this place, one has to get to the heart of the neighborhood via a busy street in Kampala: Port Bell Rd. The main market serves as the flagship and then, as you enter the slum with its unpaved streets, potholes, and boulders as obstacles, you find an oasis of fun, learning, and social development.

Kitintale’s neighborhood library opened its doors in 2022 and since then it has become a meeting point for children to enjoy their time and learn what they sometimes can’t at school; doing homework, reading, writing, talking, drawing, dancing, turning a computer on or off, creating a Word or Excel document and telling stories are some of the activities that take place in this space.

There is no set schedule, no contracted teachers, and no librarian to accompany the days but there are volunteers from the community who take turns to teach the programs and contribute to their neighborhood as best they can.

The Idea

During the Covid19 confinement, Ugandan public schools were closed between 16 February 2020 and 31 October 2021, making it one of the longest confinements in the world: 83 weeks without school.

Children were forced to suspend their studies, then with the support of some volunteers from the neighborhood and a teacher from a neighboring international school, Oscar Monti, in 2020 some reading and writing sessions started to take place in the workshop next to the skatepark, a small room that serves as an informal creative space where neighbors gather to create crafts with recycled material, design or intervene clothes, make cups or simple household utensils with bamboo or paint.

The community began to see these informal learning gatherings as a solution to the blatant unschooling of their children.

This idea was maintained thanks to the collaborative work of those involved, but it was not enough to meet the needs that the state should have.

The leaders of the neighborhood, led by Jackson Mubiru and the support of Skate Aid (a German organization that promotes skate culture around the world) received money to build the library.

At the end of 2022, with a massive donation of books and furniture from the Ambrosoli International School where Oscar Monti is a teacher, the library opened its doors.

A container of books and opportunities for learning: reading, writing, pronunciation, access to technology, stories, and dreams.

4 wheels and a lot of asphalt

The skatepark has been Jackson Mubiru’s dream for more than half his life. In 2005, he couldn’t stop thinking about the sport he saw on TV and which seemed so attractive and yet so alien to him. He became obsessed and then the universe began to tell him which path to follow to enter this universe.

He, who is a dreamer, an innate leader, and a visionary, listened. Without being very clear about how and with few material and emotional resources, he started to build the first ramp to shoot. In 2006 the signs continued to appear in the form of partners who, like him, are true to the passions of the heart.

He met Shael Swart a young South African who was finishing high school in Kampala at the time, and Barian Lye a skateboarder who was a Canadian student traveling in East Africa. With them, he not only designed and built the first skateboarding ramp in East Africa but began to document this history that 17 years later is still exciting and at its best.

The Skatepark has been home to local youth who, like Jackson, have fallen in love with the metaphor of the sport: get up as many times as it takes. Get up and try again. Fly if you have to.

A sport that has allowed the community to think of other possibilities for the use of free time and to cultivate with discipline a sport that today is recognized by the Olympic Committee.

In Uganda, you still have to make your way, step by step, with a lot of patience when you want to introduce a new idea.

This sport, unknown to many, has broken through the certainties of the sports commissions in the country and even today Jackson and his team at Uganda Skateboard Union have to face the obstacles in every process they start, explain what the discipline consists of, and infect with curiosity those who try to attack with assumptions about the danger of the sport, so that they know its advantages and allow the equipment that volunteers and donors send to the country to pass through customs without problems and so that the payment of taxes does not become an impossible obstacle to pass through.

All to be done through informal education

Thanks to the support of Jackson’s family, the collective efforts of Skate Aid, and community work, what happens around this space long ago stopped being just the practice of a sporting discipline and became a model of social development that today provides the community with spaces for economic growth, acquisition of vocational skills, effective use of public space and harmonious living.

Donations of books, computers, and other materials have arrived in a short time thanks to the efforts of volunteers, the French embassy in Uganda, private companies, and the neighbors themselves.

However, sustaining learning space forces one to question the economic dynamics of those involved in it, and this is where the project begins to falter.

Two main teachers volunteer their time to teach writing and reading to the younger children and computer skills to the older ones. Volunteers keep coming and going, but there is no guaranteed structure when it comes to project continuity.

How do you sustain a social project of this caliber without constant and projected financial and structural support? Jackson and the teachers talk hopefully about this project; it is real and tangible the potential that the bookstore, the skatepark and everything around it have for the community, even for the country.

Telling and being the story

This library is a meeting place, a place of integration, and a showcase of resilience and passion. Today, more than 100 children and teenagers from all over the neighborhood, and even neighboring around, are coming here to enjoy a book, learn something new and cultivate their imagination. Skateboards and letters inspire them to tell their story, recognize themselves as important, share their dreams, and believe that it is possible to achieve them.

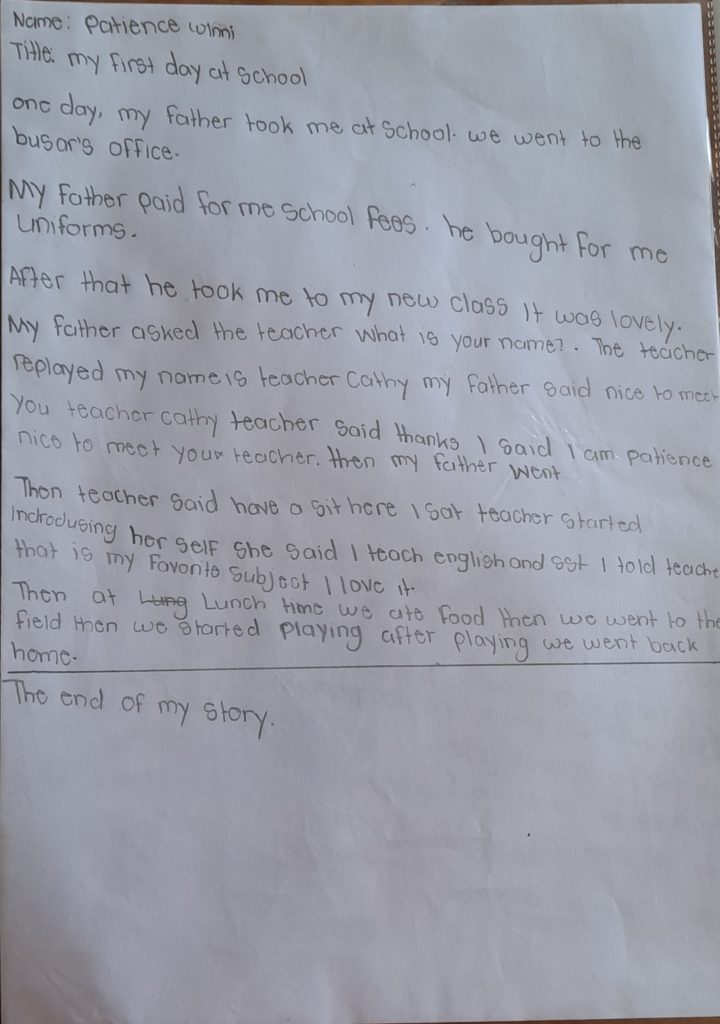

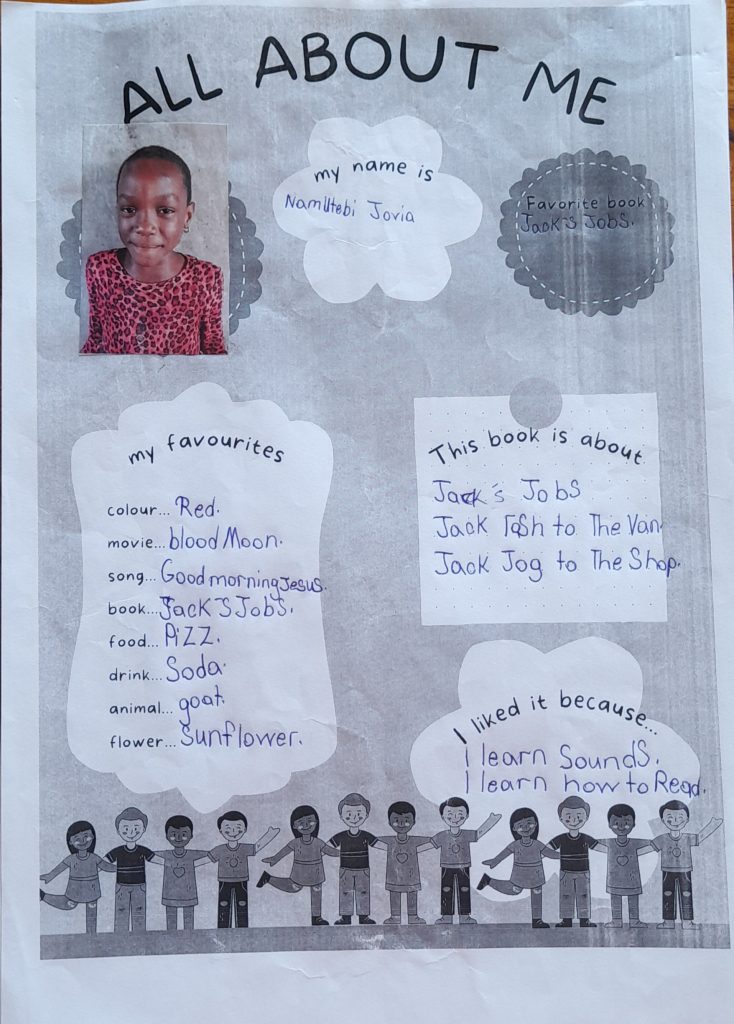

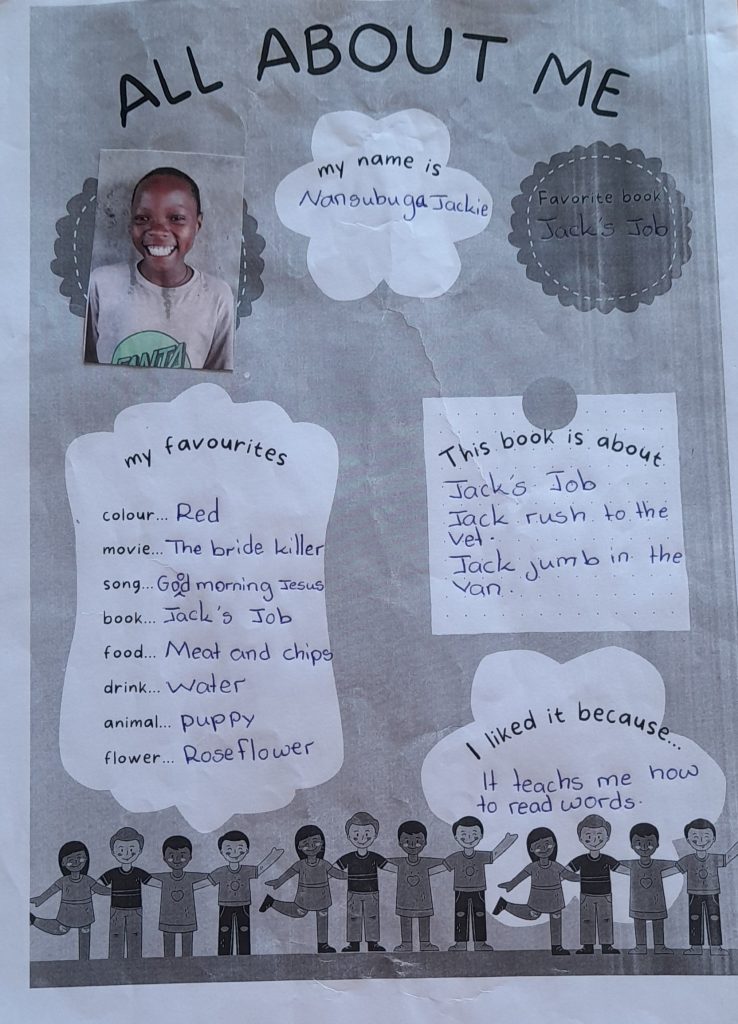

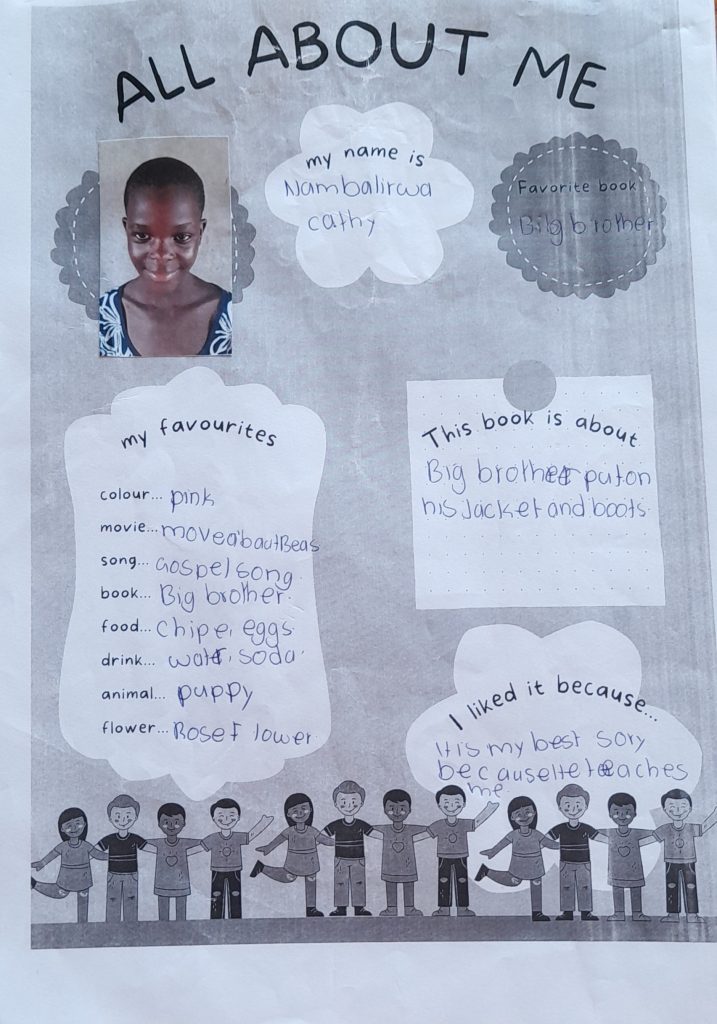

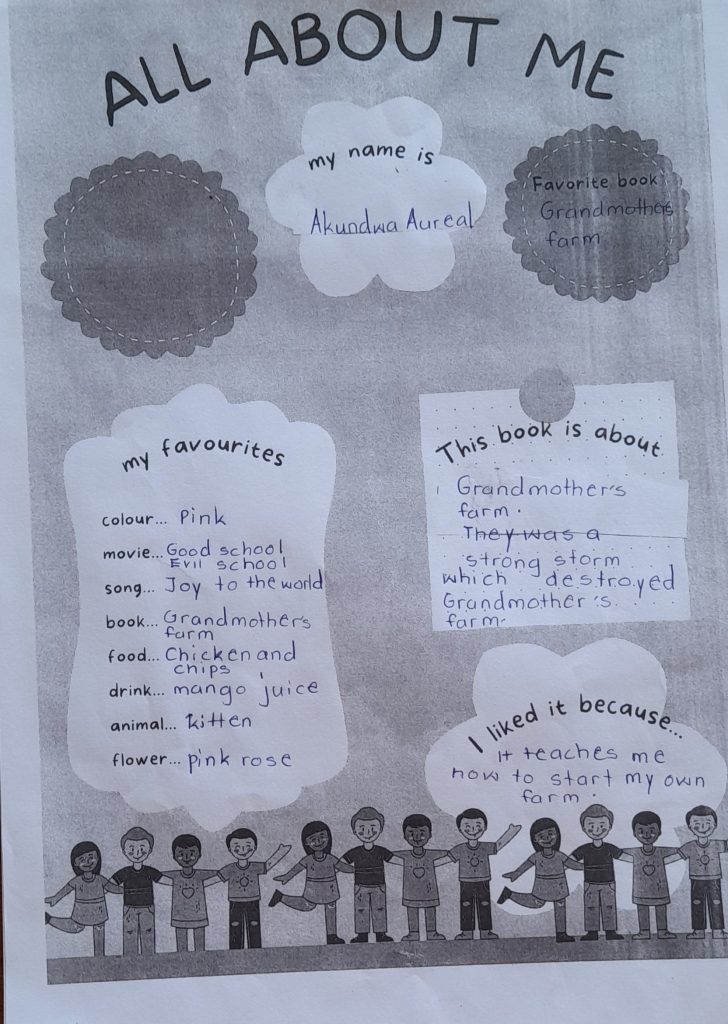

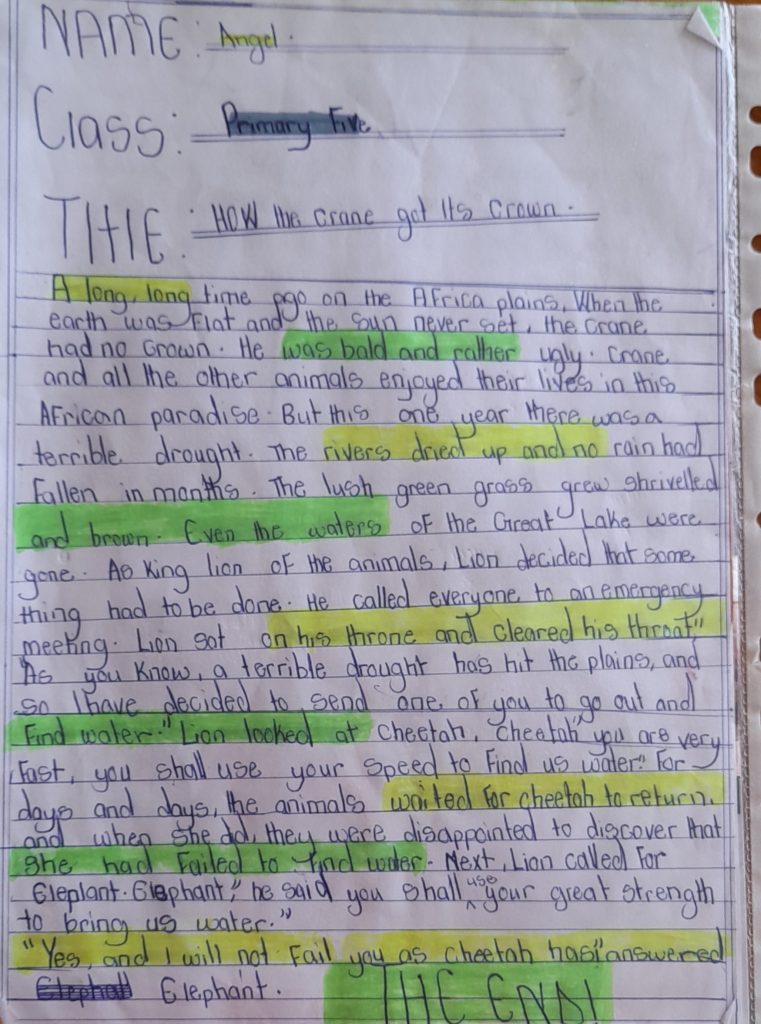

During my visits to the library and skate park, I carried out, in collaboration with Waswa Pons, one of the volunteer teachers in the neighbourhood, a storytelling workshop in which the children who attended learned a little more about creating, telling and sharing stories.

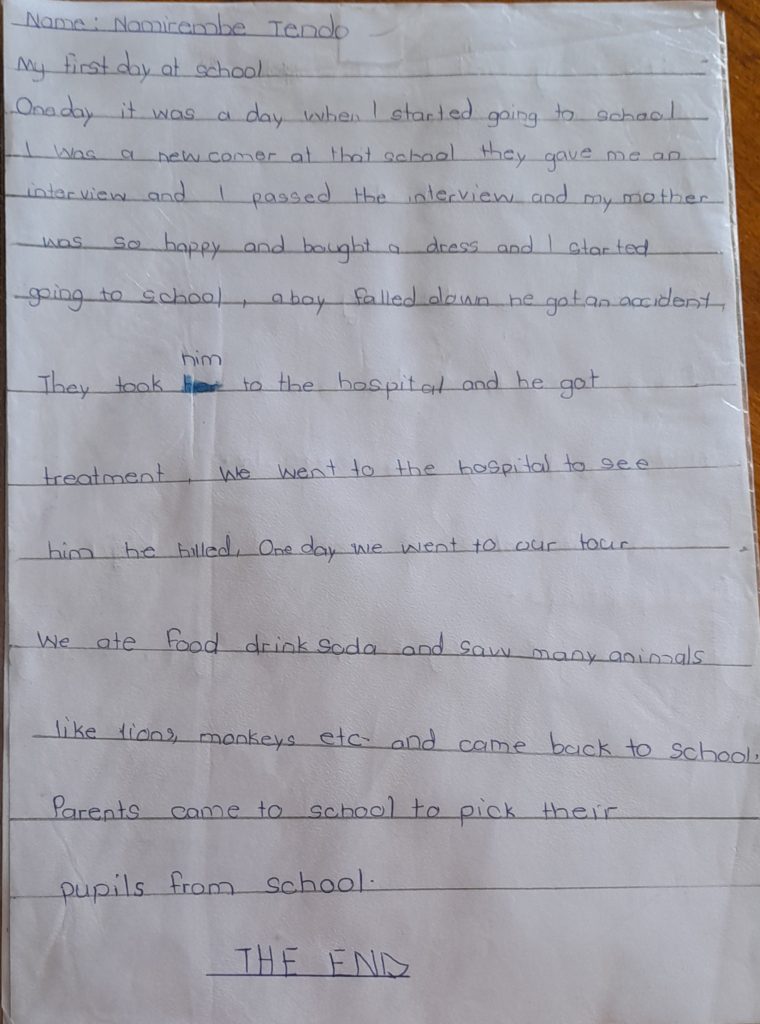

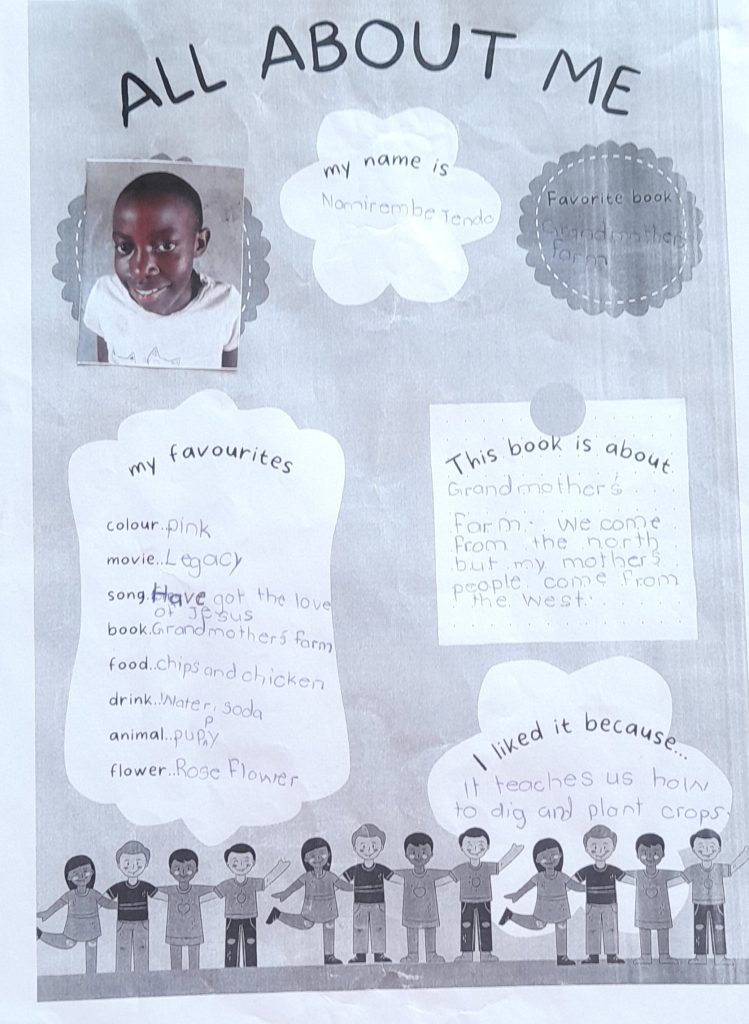

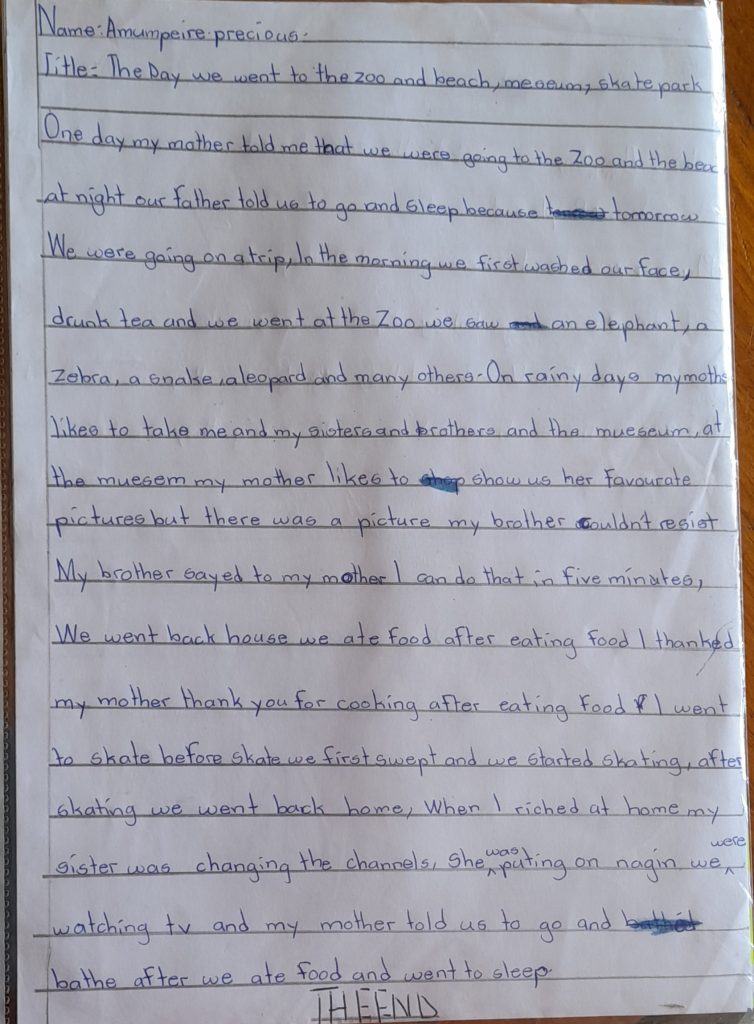

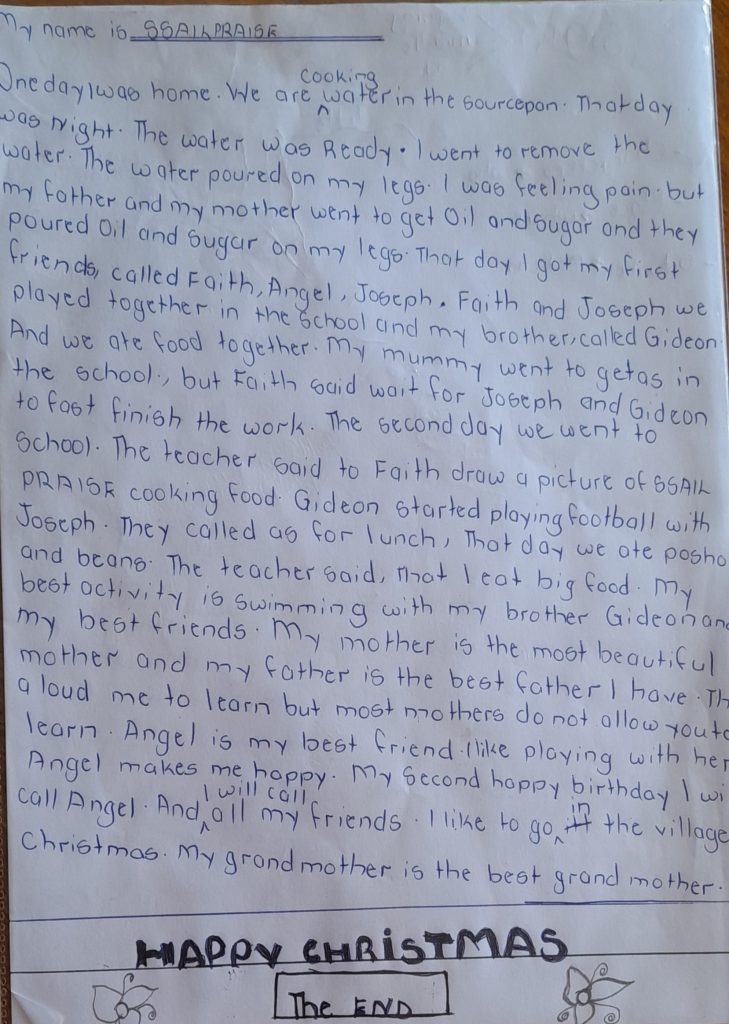

This is a small sample of their creativity.

See each child’s profile and initial story.

During 10 sessions the children learned to tell their own stories; they wrote, acted, and creatively shared their ideas about the library and the state park.

This was a joint work I did with the teacher Waswa as a process of adaptation and integration to the new space they inhabit.

Seventeen years ago the bush behind Jackson’s mother’s house was just dirt and stubble. Kampala is rapidly changing and its neighborhoods are the proof of the city’s effervescence: projects that question its inhabitants, that create services for their needs, that don’t stop when the Government abandons them and that always want the best.

Today this territory in Kitintale allows its abundance to be seen, recognizes its beauty, and shares its achievements with the whole city: a small ecosystem of social development in the heart of the Ugandan city where creativity, sport, and books are giving wings to the dreams of its inhabitants.